Home \ Knowledge Hub \ Focus on \ Focus On… Lumpy Skin Disease – A New Threat to Europe

01 Jan 2016

Focus On… Lumpy Skin Disease – A New Threat to Europe

SHARE

ALASDAIR KING

Executive Director, International Veterinary Health

The disease

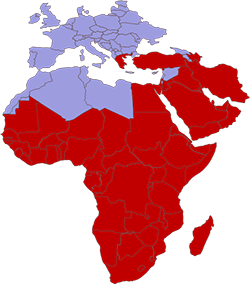

Lumpy skin disease (LSD) is an economically important disease of cattle, resulting in major losses due to damaged hides, deteriorating condition and high morbidity following outbreaks. Since 2010, the disease has been spreading and is no longer restricted to Africa. A large number of previously unexposed animals are now at risk, and as the disease moves into areas with immunologically naïve animals, there is real danger of serious epidemics.

LSD was first described in Zambia (then Northern Rhodesia) in 1929, and continued to spread in a series of devastating epizootics affecting cattle in most southern African countries. The disease extended northwards through sub-Saharan Africa, and spread to Egypt in 1988 as a result of the trade of animals and animal products; cattle movement; and favourable climatic conditions affecting vector populations. LSD is no longer confined to Africa, but has been spreading throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asia since 2012. In 2015, the disease was identified in Greece and there is significant risk of further spread in Europe.

The LSD virus is transmitted by blood-feeding arthropods which appear in high numbers when climatic conditions are favourable. Mechanical virus transmission by Ixodid ticks has also been demonstrated recently.

The disease is characterised by nodules on the skin, mucous membranes and internal organs. It is accompanied by fever, emaciation, enlarged lymph nodes, oedema of the skin, and sometimes death. It is the characteristic pox-type lesions of the skin that give the disease its name. The role of wildlife in the epidemiology of LSD is not exactly known, although LSDV-specific antibodies have been demonstrated in various wild ruminants, including African buffaloes, blue wildebeest, eland, giraffe, impala and greater kudu. The disease does not affect humans.

Virus classification

The LSDV belongs to the genus Capripoxvirus, of the family Poxviridae, comprising of the sheep pox virus, goat pox virus and LSDV.

Capripoxviruses are large complex particles of approximately 300 nm, with a genome composed of a single linear double-stranded DNA molecule of about 150kbp. Phylogenetic analysis has shown a close homology between the three viruses of the Capripoxvirus genus, as they share 96–97% nucleotide identity, although they are distinguishable through genes controlling virulence and host range. It is difficult to distinguish viruses within the genus based on serological assays, as these show considerable cross-reactivity.

Vaccines Against LSD

The first Lumpy Skin Disease vaccine was made from a strain isolated during a disease outbreak in the mid 1940’s in South Africa. It was named according to the owner’s farm where the virus was found; hence Neethling strain. Attenuation of the Neethling LSDV vaccine master seed was initially done in the later 1950’s and early 1960’s at Onderstepoort Veterinary Research Institute, South Africa, on repeated passages on the chorio-allantoic membrane of hens’ eggs followed by propagation in primary bovine cell cultures.

While some vaccines still use the original Neethling strain, others use virus isolated from subsequent outbreaks. These are also named after the site of origin, eg, the SIS strain. However, nucleotide sequencing and phylogenetic analysis using Capripox-specific primers of the viral attachment protein gene demonstrate a 100% homology with published data of Neethling-type viruses. Therefore, these other strains are referred to as Neethling-like. It is important not to confuse these with vaccines that have been developed from sheep or goat pox virus.

When considering the purchase of LSD vaccines, there are a number of factors that must be part of the decision. As well as ensuring that the vaccine uses a Neethling-like strain, a key component is the cell lines that are used to grow the virus itself. The original vaccine was grown on primary cell cultures, and this process is still in use today in some cases. The drawback of primary cell cultures is that they need to be constantly replenished, as they only survive for approximately 7-8 passages. Therefore, new cells are sourced from abattoirs, and there is a risk of introducing pathogens such as BVD or mycoplasma to the growth medium. Growing the virus on continuous cell lines is now an alternative available for some vaccines. As continuous cell lines do not need replenishment from external sources, there is no risk of contamination.

Purity of vaccine is also important. Early vaccines appear to have led to high levels of post-vaccination reactions – in some cases, undermining the use of the vaccines, as they were thought to cause signs similar to the disease itself. This can be largely overcome by manufacturing processes that filter out the excess cellular debris and ensure low levels of additional protein material. In these cases, the level of reaction has been reduced to insignificant levels. Such vaccines have been demonstrated to be safe in pregnant and lactating cows.

For countries not experienced with LSD vaccines, it is important to ensure that any imported vaccine has been tested as safe and highly immunogenic. Potency studies in calves can indicate the product’s ability to protect cattle against a virulent field strain of the lumpy skin disease virus. It is therefore worth requesting evidence of neutralising antibodies and protection at the relevant dose, as well as asking about production methods and cell lines.

ALASDAIR KING

Executive Director, International Veterinary Health